Life of an object

It’s safe to say that one of the most important part of C++ is how an object is created and how it is destructed. Let’s explain it. To understand the runtime behavior and logic, firstly we need to understand the resource model of an C++ object.

Resource model

An object contain resources: memory, file descriptors, sockets, threads, timers, etc.. Those resources are managed using RAII by object. For now we only consider the memory part, which is also the most complicated. An object manages memory in two ways:

- Direct management: memory is together with the object itself

- Indirect management: memory is managed by pointers

Resources are managed recursively

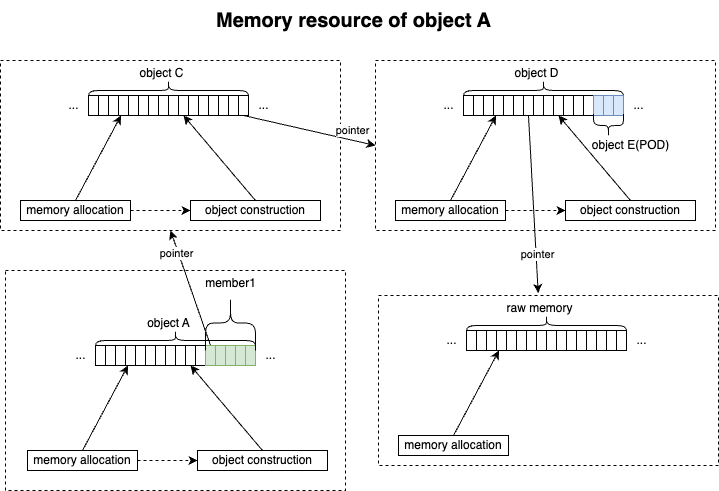

Following diagram illustrate an example of memory resources of object A. object A contains one member called member1, which is directly managed by object A; Inside member1 there is a pointer points to object C, which is indirectly managed my member1; Inside object C there is again a pointer which points to object D, which directly manages object E and indirectly manages a chunk of raw memory.

Above example is just an illustration, as we can see: it goes recursively. An object can directly or indirectly manage a huge mount of resources in this way. Another important point is that through pointers, a fixed sized object can manage variable amount of resources at runtime: this is actually the cornerstone of how dynamic languages are implemented using static languages like C/C++. It is also the basis for any program written in static languages that can dynamically manage resources.

Every object is responsible for it’s own resoruces

Every object is single-handedly responsible for it’s own resources: both directly managed resources or indirectly managed resources. In our example, member1 is directly managed by object A, so when object A is constructed or destructed, it’s responsible for allocating memory for member1, calling constructor of member1, calling destructor of member1 and deallocate memories occupied by member1. Object A does not know and care anything about object C, object D, or any raw memory. Those are recursively being taken care of by the object to which they belong.

Object creation and Object destruction operators

Creation of an object involves two distinct stages:

- Memory allocation: allocate fixed-sized amount of memory required to hold the object

- Initialization: calling constructor on pre-allocated memory region

Destruction of an object involves two distinct stages:

- Destruction: calling destructor of the object

- Memory deallocation: return the memory occupied by this object to kernel

new and delete

The new keyword does memory allocation and initialization at the same time

The delete keyword does call of destructor and memory deallocation at the same time

operator new and operator delete

The operator new only allocate the required amount of memory for an object

The operator delete only deallocate the memory occupied for an object

placement new and calling destructor explicitly

Placement new call constructor of object directly in pre-allocated memory region. Generally, the memory is individually managed by memory pool or something. After the object fulfils it’s mission, destructor of it must be explicitly called programatically by programmer, which is almost the only circumstance where destructor is called by programmer. Two important point here:

- Placement new does not allocate memory

- Call of destructor does not deallocate memory

The std::uninitialized_copy function can be used to do range of placement new on a sequence of pre-allocated memories.

Runtime creation and destruction

Now we know the memory model and the creation and destruction phase of object, now let’s consider them in action.

Recursion, again

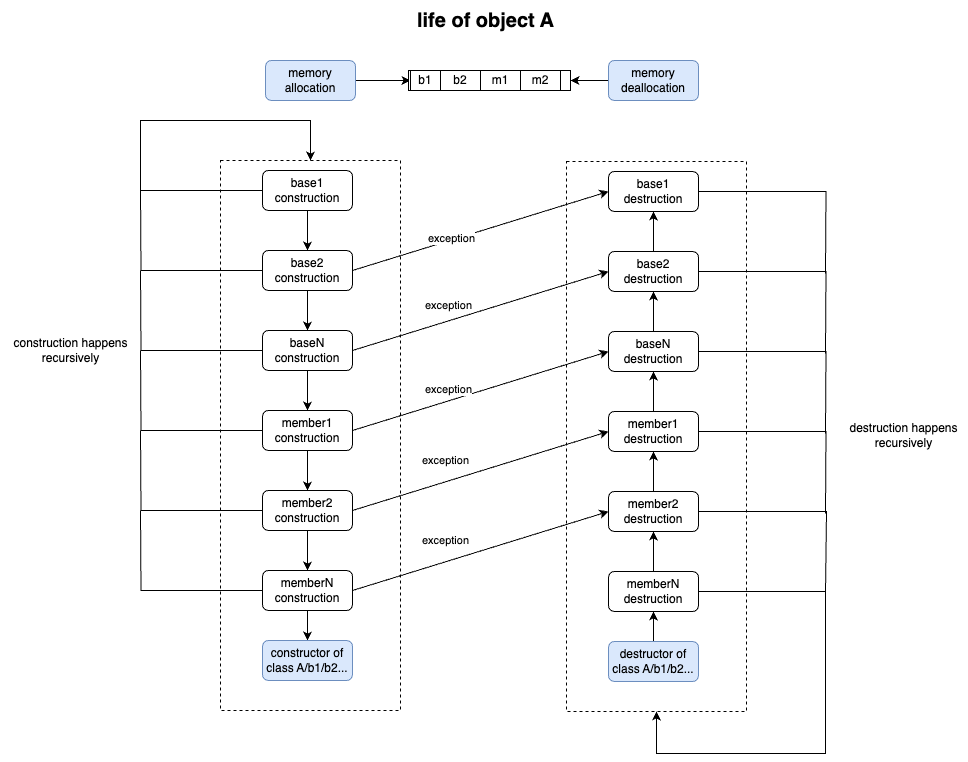

Since the resouces are managed recursively, so does the creation and destruction of object. Following diagram illustrate the creation and destruction of object A. (Note this is not the same object A above)

Let’s first ignores the exception part of this diagram and only focus on the creation and destruction part:

- The blue part: memory allocation/deallocation/constructors/destructors are the only phase that code are being executed

- Other part only indicates logical sequence of program execution

Firstly, memory has to be allocated before calling of constructors, one thing to note:

- Memory allocation happens once for object A

- All memers directly managed by object A are constructed on pre-allocated memory similar to placement

new

Secondly, since it’s a recursion, then what is the base case? Answering this question make us see through a lot of mistories of object creation/destruction. In simple words, the recursion base object meet following requriements:

- This object do not have parent class

- All members(if any) must be basic types in C++, which can be zero-initialized by the compiler

- This object have compiler-synthesized constructor or user-defined constructor

An object that meet above requirements is where the recursion ends, both for construction and destruction.

Here comes exceptions

What if exceptions occur during the construction phase of object? The behaviors are:

- Destructors should not throw exceptions ever

- If exceptions need to throw in constructors, the best way to do it is throw it directly, no better alternatives

- If an exception is thrown from an constructor:

- The destructor of the object being constructed will not be called, since it is not considered an object

- The already constructed base class, members constructors will be called in reverse order of their construction

- If the object is created using

new, the memory will be deallocated by the compiler, so no memory leakage - If the object is created using placement

new, the memory will not be deallocated

Since destructors of current object whose constructor throws will not be called, program should always use RAII instead of store a pointer to manage resources such as memory, for example:

struct MyClass {

std::unique_ptr<int> data; // good, memory will be freed using RAII

int* bad_data; // bad, memory leakage

MyClass() : data(new int(42)), bad_data(new int(43)){

std::cout << "MyClass constructor\n";

throw std::runtime_error("Error during construction");

}

~MyClass(){

delete bad_data; // This will not be called if exception is thrown in constructor

}

};

Why destructors should not throw exceptions?

It is not that destructors can not throw exceptions. Destructors indeed can throw exceptions and can be catched, as long as at the time the destructor throws there is one corresponding try..catch block waiting to handle this exception. The try..catch blocks can be nested in multiple levels, but there must be only one exception expected inside each try…catch block.

If destructors are called during unwinding, which indicates that there is already an exception existing and the runtime is trying to find a try..catch block to handle it. In this case, if the destructor also throw an exception, there is an question that can not be decided by the compiler: when a try..catch block is found, which exception should it handle? The original one, or the new one thrown by the destructor? Instead of doing this decision, the compiler just call std::terminate. Again what if multiple destructors all throws, what the compiler should do about those exceptions?

The situation is not the same if there are nested try..catch blocks. If inside destructor that is new try..catch blocks, then inside this try block if any exception is thrown, it is clear for the compiler that any exception inside it should be handled by this try block, not conflicting with the unwinding exception. In this case, the exception and it’s handler is clear.

So the question of why destructor should not throw is quite simple: one try..catch block can only handle one exception at runtime, if there are two exceptions at the same time, the compiler do not know which one to handle, so it terminate the program, which is reasonable. And the only scenario that this could happen is during the unwinding phase of an exception, during which time the destructors will be called. So destructors should take the burden to not throw exceptions.